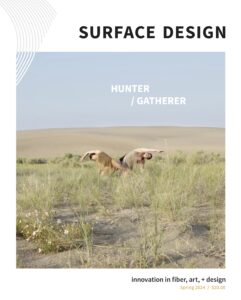

Hunter / Gatherer: Spring 2024 SDJ, Out Now!

May 13, 2024

Surface Design Association is excited to announce Hunter / Gatherer, our Spring 2024 edition of Surface Design Journal. “As hunter-gatherers, our paleolithic forebearers foraged natural resources until about 12,000 years ago when archaeological evidence of agricultural practices started to appear. Our nomadic lifestyle waned as humans built permanent settlements and domesticated plants and animals. This issue of Surface Design Journal highlights the relationship between performance art and natural dyes: a relationship that centers on beauty, ritual and tradition. Combining these two practices is a way to honor our natural world.” – Elizabeth Kozlowski, Surface Design Journal Editor

Here’s a preview of what you’ll discover:

The Chala Project by Gabriela Nirino: “Corn is the second-most important cereal crop in Argentina and the husk is often thrown away in the field. In researching, we found a lot of information about corn, but nothing specific about the husk: it was invisible, an undifferentiated part left after harvest. So we turned to craft wisdom and found María del Carmen Troncoso, a fifth-generation artisan who knows how to work with chala. She taught us the traditions of chala dolls and basketry, in which strips of different thicknesses are rolled and twisted. Although this method makes it possible to develop a continuous rope by overlapping the strips of material, it is not enough to produce a fine fiber that can be spun. At the same time, we collaborated with a spinning mill which did tests on a factory carder, mixing the material with wool. We also conducted tests with manual carders. In both cases, we achieved quite fine fibers, but failed any attempts to twist them together in a continuous yarn.”

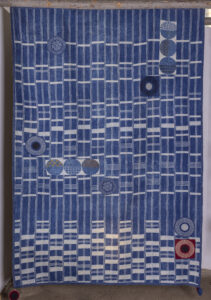

Woven samples direct dyed with indigo, turmeric, sorghum, cochineal, 2020. Photo: Damian Wasser.

Figurative Art of Decorating Textiles: Kalamkari by Chitra Balasubramaniam: “Textile decoration encompasses a range of forms, styles and techniques. One compelling practice is the Kalamkari from India. Kalamkari is a fusion of two words: kalam meaning pen and kari meaning work. It beautifully combines the form of painting, or more precisely drawing, with the art of natural dyeing. This particular technique was traditionally used for temple cloths,1 screens, wall panels, props for storytelling and as trade textiles. Modern interpretations are widely used as art, apparel, accessories and furnishing. So intricate is the drawing and coloration that at times it becomes difficult to separate the figures in the painting and see all that’s going on.”

K. Siva P Reddy, Materials used to make Kalamkari, 2023. Seeds of myrobalan, bamboo paint brushes, alum and more. Photo: Amit Goyal and Vishakha Agrahari, MeMeraki.

Natural Dyeing Against The Anthropocene: Sasha Duerr’s Participatory Classroom Within the Possible by Laurin C. Guthrie: “Duerr’s natural dyeing practice relies heavily on experimentation with whatever plants are immediately available, using the basic formula of water, dye material and fiber to create color. The emphasis for Duerr is on drawing connections between the dyer, the constituent parts of the dye and the process, all of which are specific to the location in which the dyeing occurs. To Duerr, ‘working with plant color is one of the easiest and most accessible ways of connecting with the cycle of our ecologies…’”

Sasha Duerr, Plant Palette: Seaweed, 2020. Natural dyed silk and wool with seaweed used as dye material. Photo by the artist.

Crafted Narratives and Performative Artistry of Traditional Textiles in Pakistan by Sadia Kausar: “‘Rili’” are the patchwork or applique bedspreads and quilts meticulously handcrafted by women across generations. Originating from the Sindhi word ‘ralannu,’ meaning to cover, join, and connect, the craft of Rilli making has been passed down since the Mohen-jo-Daro and Harappan civilizations (circa 2600 BCE). Rillis provide an affordable and sustainable alternative for insulation on cooler desert nights and also serve as symbols of hospitality and regard when gifted to guests. The making of Rillis involves the entire community, especially during events like dowry making, marking the passage into adulthood for young girls who are initiated into the craft.”

Bhavna Kumari & Ghulam Rasool, Natural dyed and block printed quilt, 2024. Natural dyed, block printed, stitched and

appliquéd cotton fabric and thread, 60 x 80 inches. Photo: Mahmood Ali.

Made Aware: Place, Materiality and Performing Black Interiority by narkita: “It didn’t take long to notice the absence of Black people in Denver, Colorado. We were greatly outnumbered in the Mile High City, but with my portrait and interview series ‘Black in Denver,’ I found myself part of a subculture of Black people practicing introspection, finding solace in nature, healing and incorporating aspects of African American religious traditions into their lives. It was within these pockets of community where I was introduced to ancestral magic, meditation and yoga as a spiritual practice. The room where I practice these daily rituals and the objects found within the space are represented in my solo show, i found myself in the mountains.”

narkita, don’t remove the kinks from your hair, remove them from your brain, 2023. Performance. Photo: University of Colorado Denver Experience Gallery.

Made Aware: Dyeing Waters by Pippa van Rijckevorsel: “My project ‘Dyeing Waters’ was inspired by the use of local rivers for sacred rituals like immersing oneself in the water to wash away one’s sins. It is imagined as a local ritual where the purple colors of the Netherlands are honored using red cabbage. The bright purple pigment buried inside would be used to color our clothes on a yearly basis. In this ritual we would harvest and chop red cabbage, cook for thirty minutes, extract the beautiful pigment, add alum as a mordant, wrap ourselves in white cloth and immerse ourselves in the local purple pride. It would be a moment to honor the earth and the fruits of the land we live on: respecting the naturally fading pigment, knowing that the day of harvest and thus bright color will come again next year.”

Pippa van Rijckevorsel, Dyeing Waters, 2023. Installation and performance with red cabbage-dyed, laser-cut and sewn fabric, with other various materials, 120 by 80 inches. Photo by the artist.

Informed Source: Resensitizing Ourselves Through Dance by Mariah Palmer & Sara Mannheimer: “The performance engages with the tensions and dualities around land use through costumes, filming location, and choreography. We dyed the fabric for our costumes using St. John’s wort, a plant that can be invasive but is also a valuable herbal treatment for depression. We filmed on an area of land that is partially protected as wilderness and partially open to motorized four-wheeler recreation. And through our concept and choreography we explored feelings of both sadness and joy. In the sections below we discuss each of these aspects of the performance: costumes, location and choreography.”

Local Earth Collective, Grief, 2021. Dance film. Dancers: Anna Allen, Sara Mannheimer, Dorothy Burns, Ellie Oakley, Mariah Palmer, Dana Terzi. Choreographers: Mariah Palmer and Sara Mannheimer. Photo: Nathan Norby.

Informed Source: In the Shelter of a Sumac Tree by Dina Nazmi Khorchid: “‘A Msakhan Ceremony,’ much like cooking a meal over and over again, is an ongoing body of work that invites participation with food culture, politics and natural waste material, interpreted through textiles and a dinner gathering. Politically, watermelons are symbolic of the Palestinian flag in times where raising it is banned. The anemone poppy flower is a symbol of the blood of martyrs shed in sacrifice. Food wars about the origins of hummus become a humorous yet very serious debate, while msakhan—considered by many the national dish of Palestine—celebrates the olive harvest season, joyful events and communal gathering. Msakhan literally translates from Arabic to ‘heated,’ referencing distinct components that are cooked separately then assembled to birth this beloved dish, or in my interpretation, a heated argument and passionate statement of existence.”

Dina Nazmi Khorchid, A Msakhan Ceremony, 2024. Bundles of fabric and edible bread rolls on submerged and bundle-dyed silk, linen and cotton tablecloths, dyed with onion skins, sumac and pine cones. Photo by the artist.

Informed Source: Connecting Threads by Judy Newland: “What happens when you bring an eclectic group together to share their stories around a dye pot? Joy, hope and love explode into the most beautiful creations and friendships. As the cauldrons boil, we contemplate life, enjoy new experiences, and ponder art, nature, making and living. Over time, we bond over the beauty we have created or the mistakes we have made. How did this happen?”

Creative Color Collective gathering dye materials in the garden, 2023. Photo: Calvin Stutzman.

Emerging Voices: A Call to Land: by Pachia Lucy Vang: “As a HMong American, I’ve always questioned my positionality in the world. The HMong are not only a stateless people but one that have been displaced from their ancestral homelands. This absence of place is combated by the ways we have imbued our national identity into textiles. The cultivation of my own voice through cloth rekindles a relationship to land while tapping into complexities around race, culture, diaspora and belonging.”

Pachia Lucy Vang, peb teb, teb peb: a call to land, 2023. Appliquéd, embroidered and reverse-appliquéd madder and turmeric dyed silk with gold leaf, 2 x 2 feet. Photo by the artist.

In The Studio: Musubi 結び // Connections by Maki Teshima & Alexander Liss: “The central idea of ‘Musubi’ was to create connection: connection between nature and urban life (at Steele Elementary School, at the busy intersection on Alameda Avenue and Marion Parkway); and also connect tradition and modernity, by re-examining the traditional Japanese concept of musubi and allowing me to reconnect with my heritage. My vision was to create a collective work of art by literally connecting individuals to each other through knot-making and put that work on public display for people to touch and interact with.”

Maki Teshima, Musubi 結び // Connections, 2023. Natural-dyed t-shirts with copper pipe, hemp ropes, wood sticks, 150 x 120 inches. Photo: Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite.

In The Studio: Recipes to Perform with Spring by Clara Peterson: “The days are long and seemingly unending. Plumes of goldenrod are forcing their way through concrete and along the shoreline. While you pluck armfuls of powdery flowers, take care not to be stung by bees addicted to pollen. Soon your hands reflect the colors of life around you. It won’t be long before the indigo begins to bud, and the symphony of a life filled with color plays its last chorus. Gather the acorns and alder cones before the rain forces their tannins into the wet earth.”

Clara Peterson, Wintering Sycamore, 2024. Natural-dyed (black oak bark, oak leaves, crabapple bark, marigold, indigo and logwood), appliquéd and quilted cotton and found fabric, 20 x 36. Photo by the artist.

In The Studio: Embroidering Earth’s Elements by Katerina Knight: “Flora, with their seasonal transitions, offer a continual stream of new inspiration. In my chemical- and machine-free practice, I combine intricate hand processes of embroidery, needle lace and natural dye. Using homegrown or locally foraged materials, I gently transfer organic colour to yarn, thread and cloth or delicately stitch with the dried materials as embroidery embellishments.”

Katerina Knight, Holding a Garden in my Hands, 2023. Threaded dried flora on chamomile silk, 19.5 x 19.5 inches. Photo by the artist.

To buy a copy of Hunter / Gatherer, go to the SDA Marketplace, or you can check out a free digital sample on our SDA Journal page.