Out of Hand by Wendy R. Weiss

April 21, 2023

We arrived in Vadodara, Gujarat, India in late May 2022. The temperature was over 110 degrees fahrenheit, but the town was familiar: we had lived in the city on three previous stays. My husband, Jay Kreimer, was working on a Fulbright-Nehru project creating invented musical instruments from common Indian materials found in local markets. I brought recent warp ikat and natural dyed weavings that I was planning to exhibit in Hyderabad and Vadodara. Previously, two Fulbright-Nehru research awards allowed me to investigate ikat weavers in Gujarat, documenting their work from an artist’s perspective and Vadodara had been our base.

Wendy R. Weiss, Hand (detail), 2022. Cotton warp dyed with Indian madder, marigold and ferrous. Photo by the artist.

Bina Rao (Creative Bee) hosted a weaving exhibit and musical performance for us at Saptaparni in Hyderabad and Kavya Oza organized a show at the Distillery Gallery at Space Studio in Vadodara. For the Distillery Gallery I made a new piece called Hand, based on ikat, using natural dyes, text, and pattern.

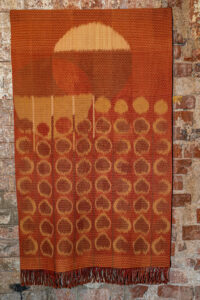

Wendy R. Weiss, Darkness Moving to Light, 2021. Cotton warp ikat with natural dyes. Photo by the artist.

Artists and curators we met were surprised to learn that we made the work ourselves, by hand. Indian weavers work with their hands—and feet—to complete tasks related to weaving and the loom, and I wanted to express my respect for their work. Since I often use ikat text in my weavings, I selected the word hand, to be the centerpiece of the ikat warp installation.

Wendy R. Weiss, Hand, 2022. Cotton warp dyed with Indian madder, marigold and ferrous. Photo by the artist.

To frame the text I used a yellow and red pattern inspired by my study of mashru. Historically, mashru (which means permitted) is a satin weave fabric with a silk warp and cotton weft. This structure made the fabric acceptable for Muslim men to use in clothing because the cotton weft touched the skin, while the decorative silk warp faced the world. In other words, silk was not allowed to touch the body. I first saw examples of mashru at the Calico Museum, Ahmedabad in the 1990s. Since then, I have been studying this fabric from illustrations in museum digital databases and 19th century texts that record examples of Indian fabric collected for international exhibitions in the colonial period. Ikat mashru was made with a variety of patterns, predominantly arrowhead and kanjara (wavy line) patterns. I have speculated about how the binders tied the ikat in order to make these simple, yet dazzling patterns, based on what I learned about binding warp for ikat in Gujarat with master weaver Vitthalbhai Vaghela.

Hand-dyed warp for in Indian madder, Karan Patel’s farm, Aanushrav, 2022. Photo: Wendy Weiss.

The tall ceiling and spaciousness of the gallery lent itself well to a suspended work. I determined that I would wind, bind, and dye individual warp chains with natural dye, in preparation for weaving, but would stop the process after the dyeing and hang the warp as lengths of dyed sets of thread. I hoped to show the process of ikat rather than weave an ikat. The famous Patola, or double ikat, is well known in the area. It is woven in the town of Patan just 170 miles to the northwest of Vadodara, but the general public is not familiar with the ikat process. Once we estimated the height of the truss in the space, I began winding 42 warp chains with cotton thread I purchased in the city market bazaar. One 100g ball of thread yielded a warp chain of about 80 threads, varying in length, but roughly 180 inches after shrinkage.

Staff installing Hand at Distillery Gallery, Space Studio, Alembic City, Vadodara, Gujarat, 2022. Photo: Wendy Weiss.

Natural dye has been an essential part of my studio work since I converted to plant based dyes twenty years ago. Early one morning my husband and I went to the city market to purchase 10 kilos of marigolds, which I set out to dry in one room of our flat. I wound the warp in the weaving studio of the Textile and Clothing Department of the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. I scoured, mordanted, and dyed an initial layer of marigold yellow at home.

Wendy R. Weiss, Red and Green Weaving (in progress), 2023. Handwoven and naturally dyed with weld, indigo and madder. Photo by the artist.

The remaining dye work was too large-scale for me to complete on my own in the flat. With natural dye friends, Vrushali Lele and Karan Patel, we completed the dyeing at Aanushrav, a sustainable farm and dye site near Anand, using Rubia cordifolia, Indian madder, and ferrous acetate that Karan made. Vrushali created a short video documenting the process of making Hand.

Warp is wetted out and prepared to dye in Indian madder, Karan Patel’s farm, Aanushrav, 2022. Photo: Vrushali Lele.

The show, titled Out of Hand, included a sound score and performance by Jay Kreimer and paintings and sculpture by Lauren Bechelli. I am grateful to the host venues who allowed me the chance to show some of my weavings in India and to the people who came out to see the work, especially the weavers.

–Wendy R. Weiss exhibits her work in solo and group shows in North America, Europe, and Asia. She is an editor for the Journal of Textile Design Research and Practice, professor emerita of textile design, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, past recipient of two Nebraska Arts Council Artist Fellowships, and a Winterthur Residential Fellowship.