Traditions & Techniques in Beading: Winter 2022 SDJ, Out Now!

December 28, 2022

Surface Design Association is excited to announce our final Journal of the year: Traditions & Techniques in Beading, Winter 2022 edition of Surface Design Journal.

“This issue takes us on a journey across time and space—from contemporary North America and Uganda to China in 2700 BC, to planets and stars billions of light years from earth—to celebrate the traditions and techniques of beading.” – Elizabeth Kozlowski, Journal Editor

Here’s a preview of what you’ll discover:

“Party Beads” by Rebekah Frank: “Craft and hobby stores are more than a place to pick up tools. They are also a supply store for building memories, where party planners find the decorations to mark life’s many milestones. Everything one needs to transform a mundane space into a celebratory, immersive experience can be discovered in craft store aisles. These materials tend toward bright colors, reflective surfaces, and inexpensive plastics. In the hands of artists, these materials transform into visually vibrant conversations about identity, place and cultural belonging.”

Kelly Dzioba, Polychrome (folded), 2022. Toy bead necklaces, 16 x 16 x 1 inches. Photo by the artist.

Aya Rodriguez-Izumi, Black Shiisa, 2018. Mylar, debris netting, fabric, sharpie, acrylic beads, zip ties, safety pins and thread, 37 x 65 inches. Photo: JSP Photography, courtesy of the School of Visual Arts.

“Nafis M. White’s Homage to Black Women’s Steadfast Creativity Through Braiding and Beading” by Paulette Young, Ph.D: “Beads—colorful, roundish forms that reflect and transform light—are encoded with meaning and power. They are used worldwide as talismans, status symbols and spiritual artifacts and as a measure of commerce. Beads tell a story as they travel across cultures, space and time. For the visual artist Nafis M. White, beads play a central role in her rich, vibrant, bold and tactile installations. White draws on the histories and traditions celebrating and honoring Black women’s innovation, imagination and steadfast creativity passed across time with their fingertips through weaving, braiding and beading.”

Nafis M. White, A Burst of Light (Red), 2018. Hair, embodied knowledge, ancestral recall, audacity of survival and bobby pins, 105 x 51 x 16.5 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and Cade Tompkins Projects.

“An Everyday Chat About David Chatt” by matt lambert: “‘The everyday’ summons up the most mundane practices in our lives while simultaneously challenging place, position, class and all the social markers that define us as individuals. Artist David Chatt approaches the everyday in the forms of domestic objects, handwritten letters, toys and the detritus overlooked on a daily walk and physically skins these things with beads as a mechanism to slow the viewer down. Beads become a masking or cloaking device that encourages the viewer to meditate on the silhouette of form and imagine the potential of detail now netted and captured inside.”

David Chatt, 1982, 2015. Found objects covered in sewn glass beads on a wooden table, 40 x 30 x 12 inches. Photo: Mercedes Jelinek.

“Contemporary Indigenous Beading” by Dr. Manuela Well-Off-Man: “Indigenous people have been practicing the art of beadwork for centuries; however, recent exhibitions illustrate this artform has claimed its rightful place in the contemporary art world.1 In pre-colonial times, Native American artists created their own beads using bones, shells, teeth, copper, and other materials. When glass beads became popular as trade goods in the 18th century, beadwork started to become one of the most iconic Indigenous art media.”

Teri Greeves (Kiowa), Great Lakes Girls, 2008. Glass beads, bugle beads, Swarovski crystals, sterling silver stamped conchae, spiny oyster shell and cabochons on canvas high-heeled sneakers. Brooklyn Museum, gift of Stanley J. Love.

“The Bead King” by Jessica Hemmings: “The first paper bead to catch Sanaa Gateja’s eye was in the studio rubbish bin. Gateja was studying jewelry design in London and explains, ‘I took it home and saw how it was made.’ The discarded bead revealed a rolled oval shape and the potential of recycling. But at that time, in the 1980s, power dressing ruled and Gateja feared “no one in London would buy paper beads.” Instead, he used centrifugal casting to create versions in gold or silver to sell at markets on the weekends. But the original idea of working with paper beads remained with him. ‘I kept it as a secret,’ he explains, ‘to introduce the idea to villages when I returned to Africa.’”

Sanaa Gateja, Old Coffee Tree, 2021. Paper beads on barkcloth, 85.5 x 64.5 inches. Courtesy of Afriart Gallery.

In Conversation: “Seed of Memory: The Beaded Works of Erica van Zon” by Jane Groufsky: “Textured glass windows, vintage floor tiles, the sheen of light on water: multidisciplinary artist Erica van Zon was first drawn to glass beads to depict these glistening subjects. Yet beading has now become an integral part of her practice and is just as likely to be used to illustrate a fried egg as a swimming pool. With an insatiable curiosity for technique and subject that could spool out forever if not reined in, it is no wonder van Zon has gravitated towards a material that has both inherently attractive qualities and built-in limitations.”

Erica van Zon, Autumn Leaves on Pool, 2022. Glass beads on cotton, 14.125 x 14.125 inches. Courtesy of Jhana Millers Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand.

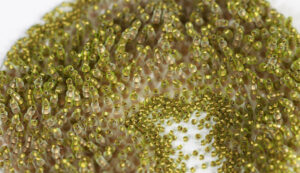

In The Studio: “Beads in the Cosmos” by Nora McGinnis: “Beads have been central to my work for many years, as a constant companion to my evolving thinking. Their glow and gleam drew me in, and I soon discovered their ability to act as building blocks: tiny units that can be stitched and woven together in different configurations. This quality lets me get my hands on the more intangible phenomena I study, understanding ideas in a different way.”

Nora McGinnis, Growth Pattern X (detail), 2019. Beading and embroidery on silk, 4 x 4 inches. Photo by the artist.

In The Studio: “Bead Buddies” by Lynne Sausele: “My journey with beaded teapots began when Mobilia Gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts invited me to make a teapot for an upcoming exhibition. The gallery was showing my beaded jewelry at that time and so I decided to make my teapot with beads, but how?”

Lynne Sausele, Oasis Teacup & Saucer, 2021. Ceramic and glass beads, 5 x 7 x 5 inches. Photo by the artist.

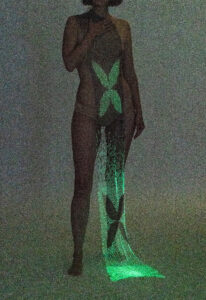

Spotlight On Education: “Beading Material and Meaning in the Parsons MFA Textiles Program” by Anette Millington: “The communal studio at the MFA Textiles Program at Parsons School of Design is buzzing with making and explorations in hybrid textiles, including a multiplicity of approaches to beading. Two recent graduates, Aradhita Parasrampuria and Alyssa Schulman, activate bead making and bead embellishment to advocate for justice and relocate our human relationship to the natural world.”

Aradhita Parasrampuria, Bioluminescent Textile, 2022. Handmade beads, jellyfish protein and thread, 12 in x 40 inches. Photo by the artist.

Alyssa Schulman, Your Knives Cut Deep: Wound (detail), 2022. Naturally dyed, knitted and bead embellished plant fiber felt. Photo by the artist.

First Person: “Beadwork: An Artist’s Choice” by Sébastien Carré: “Creating art jewelry with beadwork was not such an obvious choice at first…During the period between my bachelor’s and my master’s degree I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease. That changed everything. I could no longer sit in front of a bench for long hours, due to my greatly reduced strength caused by pain and tremendous weight loss. Because I was still possessed with my desire to create, being able to work outside of the studio became necessary. While waiting for treatments to take effect, I changed all of my processes and techniques, to find new ways to construct and design.”

Sébastien Carré, Several scales of grapes (ring), 2015. Crocheted and embroidered nylon lacework, Aventurines gemstones, beads and cotton, 2.37 x 2.76 inches. Photo: Milo Lee photography.

First Person: “Revealing the Invisible” by Lorenzo Nanni: “Inspired by counterculture, independent films, fetish photography and underground techno music, I begin naturally to orient my work around the human body, and more precisely around a movement I personally identify with: body modification. I experiment simultaneously both on my own body and on my textile projects.”

Lorenzo Nanni, Syrtensis II, 2010. Felt, wool, threads, quartz beads, french jet and seed beads, 29.5 x 21.6 inches. Photo by the artist.

Legacy: “From an Empress to a Marquise: The Journey of Haute Couture Embroidery” by Rebecca Devaney: “According to legend, the humble silkworm was discovered in China in 2700 B.C. by the Empress Leizu when a cocoon dropped from the branches of a mulberry tree into her tea. A delicate filament unraveled from the cocoon, and soon the empress, and her ladies-in-waiting developed the techniques of silk manufacture. This was a fiercely guarded secret by the successive Chinese dynasties who held a monopoly on luxurious silk fabrics and exquisite embroideries exported by land and sea along the Silk Road from 1000 B.C. Eventually the secrets of silk production were revealed and gradually spread across Asia, Africa and Europe.”

Rebecca Devaney, Professional Training in Haute Couture Embroidery, 2018. Lunéville and needle embroidered silk organza, metallic, silk and cotton embroidery thread, beads, sequins, feathers, gold foil, feathers and lamé, 15.75 x 23.5 inches. Photo by the artist, École Lesage, Paris.

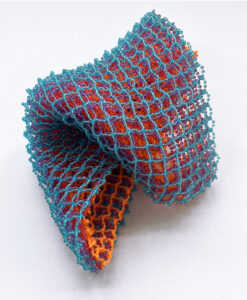

Informed Source: “A Suite of New Beaded Surfaces and Linkages” by Kate McKinnon: “During the past 10 years of discovery, the open-source Contemporary Geometric Beadwork (CGB) project I co-founded has discovered many new structures and surfaces that can be built with beads and fiber. By using (and devising) thread paths that create architectural beadwork, our research team has built many new kinds of rotating engineering linkages…”

Dustin Wedekind & Kim Van Antwerp, Nine Different Faces of a Kaleidocycle, 2016. Hand sewn glass beads using geometric peyote stitch with a variety of increase and decrease progressions, 3 inches in diameter. Photo: Kate McKinnon.

On Display: “Radical Stitch” by Katie Wilson: “Radical Stitch looks at the contemporary and transformative context of beading through the aesthetic innovations of artists and the tactile beauty of beads. Beading materials and techniques are rooted in both culturally informed traditions and cultural adaptation, and function as a place of encounter, knowledge transfer, and acts of resistance.”

Radical Stitch (installation view), MacKenzie Art Gallery, 2022. Photo: Don Hall.

To buy a copy of Traditions & Techniques in Beading, go to the SDA Marketplace, or you can check out a free digital sample on our SDA Journal page.