Unraveling the Past; Weaving the Future by Erica Hoelscher

June 30, 2023

My mother, Helen, was born and raised on a hard-scrabble farm outside of Boonville, Missouri. In this Depression-era self-sustaining household, if the household goods were to be more than simply utilitarian, they would be decorated by female family members. Clothing was constructed, altered, and refashioned, and all manner of textiles were created and beautified by various means. The family endured poverty and isolation; the act of adorning was a comfort and a creative outlet born of necessity, for every scrap was recycled to extinction.

Helen Schwartz on the steps of her childhood home, a farm outside of Boonville, Missouri 1940s.

This arduous upbringing made my mother a hard worker whose toughness was also manifested in the emotional wall that surrounded her. While she possessed innate skills with handcrafts of all sorts, she was often rigid and disapproving in her demeanor. Her relationships were restrained and limited. She taught her children clothing construction and many forms of needle arts as a way to be close to her. We wholly embraced those early art lessons as a fundamental form of emotional exchange substituting for more engaged mother/daughter relationships, and all three would ultimately pursue artistic careers.

Helen Hoelscher, Baby Sweaters, 2018, Crocheted acrylic yarn. Photo: Kristin Hoelscher-Schacker.

Shortly after her death, my father disclosed the mental health challenges Helen had faced throughout their marriage and how as a team they had sheltered us. He said, “Your mother developed a mental situation and had a level of resentment toward me. A whole new personality came out, which I did not recognize even though I still loved her deeply. She was of two minds. I always loved your mother even though she made it hard to love her sometimes.” I asked my father if my mother was mean to him, and he said, “Yes. She brought so much tension into the relationship. I would often try to talk to her about it, but she was not receptive. I would try to make a way of talking and thinking and she would get very anxious about me. She wanted to keep things private and personal, and she didn’t share with me. She was in a struggle. She had gone inside. I tried to do things differently but no matter how I changed, she would find something else to be critical about. She was so tortured. I wondered if she desired to take her own life.” With these sudden and shocking revelations, my father released decades of secrecy that helped make sense of the anxious patterns and frequent melancholy that haunted my memories.

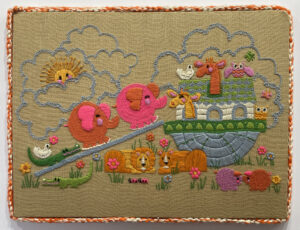

Helen Hoelscher, Noah’s Arc, 1970, needlepoint, 20 x 16 inches, personal photo.

Throughout my childhood, textiles were an everyday activity in which my sisters and I naturally partook. We received lessons from our mother and then branched off to our own creativity. Learning clothing construction filled a need because I could adjust patterns to fit my height (I’m almost 6 feet tall). Another benefit was that textiles could be pursued quietly, alone, almost in secret. During many hours of solitariness, I would complete elaborate cross-stitch projects, embroider designs of my own creation, complete macrame wall-hangings and belts, and weave on my table-top loom.

Helen Hoelscher, granny square afghan, 1980. Crocheted acrylic yarn scraps. Photo: Kristin Hoelscher-Schacker.

As a child I believed that my mother’s stress and charged emotions were caused by me—my misbehavior, my lack of understanding, my religious questioning. Acknowledging and recognizing the effects of my mother’s psychological and emotional struggles has been central to my own healing journey. In therapy I’ve learned about the effects of Childhood Emotional Neglect, and how it has inspired and affected my artistic practice.

Moliere, The Misanthrope, 2004. Costume design by Erica Hoelscher, produced by the Department of Theatre, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

All costume designers want to explore how sartorial choices reflect the inner qualities of a character, using fashion as a reflection of identity. My own rather loose perception of self facilitates my ability to identify with characters and to expose the hidden, inner world on their outer surface. A lack of firm commitment to my way of seeing things makes me a better collaborator. As an artist I’m much more intrigued by questioning my perceptions and grappling with meaninglessness than a depiction of “reality.” I strive for art that is transgressive, dangerous, ironic, and satirical. I teach artistic skills as a way of connecting, sharing, communicating, and creating knowledge with students, just as my mother exemplified.

Witold Gombrowicz, Ivona, Princess of Burgundia. Costume design by Erica Hoelscher, produced by Idiopathic Ridiculopathy Consortium, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Photo: Johanna Austin.

I now recognize the challenge it was for my mother to fully parent and be present in my life, while accepting that the past is forever incomplete. I hold the remaining examples of my mother’s creativity not only as evidence of her artistic skill but also reflections of her sometimes-tortured emotional depths. The true value of my mother’s creative legacy is to help me forge a path forward to acceptance and healing.

Helen and Erica Hoelscher, Wedding Dress and Veil, 1997. Made by Erica Hoelscher, silk satin, embroidered lace fabric, silk netting and beads.

–Erica Hoelscher is a Professor of Theatre, College of Arts and Sciences and Associate Dean for Faculty and Staff Affairs, College of Health, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA. Associate Artistic Director for the Idiopathic Ridiculopathy Consortium, Philadelphia, a theatre company specializing in Absurdism. She has an MFA in stage design from Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, and teaches courses in apparel design and history.